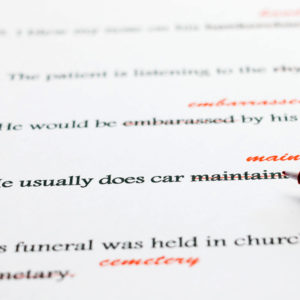

Most people know dyslexia as a difficulty with reading, writing and spelling. However, dyslexic traits can also affect other areas of a child’s life – in both positive and negative ways.

In fact, dyslexia is so wide-ranging that, while researching my book on the subject, I identified thirteen different areas of learning that can be affected by dyslexia. This list includes: vision, reading, spelling, writing, speaking, listening, maths, movement, time, organisation, music, foreign languages, and problem solving.

It used to just be called a ‘reading disability’ – not anymore!

No clear-cut definition

It may surprise you to learn that there’s still no definition of dyslexia that everyone agrees upon. Experts in the field are still deciding which learning difficulties to include in a definition of dyslexia and which ones to leave out.

Dyslexia frequently overlaps with other conditions

This is because dyslexia frequently overlaps with other related conditions, including dyspraxia (difficulty with movement) and dyscalculia (difficulty with counting).

To further complicate matters, dyslexia can also overlap with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and ASD (autism spectrum disorder), which again alters how dyslexia presents.

Whew! Confused yet?

No wonder many professionals prefer to use the umbrella term, Specific Learning Difficulties (SpLD), which refers to dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia and sometimes ADHD. These learning difficulties are specific, because they only affect certain areas of learning, as opposed to generalised learning difficulties, such as Down’s syndrome.

The Rose Review

Although no universal definition of dyslexia yet exists, the one that receives the most attention in the UK is the one created by Sir Jim Rose, in his 2009 governmental review of dyslexia.

It’s full of the kind of language that makes for perfect bedtime reading… yawn… but let’s try and get some sense of it anyway, shall we?

Here are the key points of the Rose definition of dyslexia:

Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed.

In plain English, please?

Phonological awareness is an understanding of how speech sounds relate to letter symbols. It’s basically the building blocks of reading. So, if you have good phonological awareness, you’ll find it easier to learn to read. However, dyslexic children tend to have poor phonological awareness, so may struggle to learn to read.

Phonological awareness is an understanding of how speech sounds relate to letter symbols. It’s basically the building blocks of reading. So, if you have good phonological awareness, you’ll find it easier to learn to read. However, dyslexic children tend to have poor phonological awareness, so may struggle to learn to read.

A dyslexic child is also likely to have a weak working memory. He’ll be able to hold fewer pieces of information in his short-term memory. It might take more effort for him to solve problems and make connections. And it can make it harder for him to transfer new skills to long-term memory. Parents often find that their dyslexic child can perform a task when it’s uppermost in his mind. But he won’t remember how to do it the next day.

Even when he does store a skill in his long-term memory, he may find he has problems accessing this memory quickly. Dyslexic children tend to have a slower processing speed. This does not mean they are less intelligent. It just takes them a little longer to make the connections that non-dyslexic children can make instantly.

Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities.

Contrary to popular myth, dyslexia isn’t just ‘middle class for stupid’. Dyslexics come in all shapes and sizes, from all walks of life – and at all points on the IQ curve.

It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points.

Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia.

Well, we covered this already. Even Sir Jim isn’t willing to commit himself to an exact definition of dyslexia!

A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well-founded intervention.

No form of intervention can completely erase dyslexia. Someone with dyslexia will always have dyslexia. However, a dyslexic child is not, by definition, stupid. She can be – and should be – helped to build up strategies that can speed up her learning.

In fact, when she’s given the right support and taught in a dyslexia-friendly way, a dyslexic child can make incredible progress.

Understanding the dyslexia spectrum

Even official definitions of dyslexia can seem as clear as mud, can’t they?

Every dyslexic child is different

The bottom line is: dyslexia exists on a spectrum. It may be severe; it may be mild. It may primarily affect reading, or it could more strongly affect a child’s progress in maths. Every child is different – and this means that every dyslexic child is different.

However, the good news is, they can all be supported in a way that plays to their strengths, rather than focusing on their weaknesses.

Still wondering if your child could be dyslexic? Use my 5-minute dyslexia checklist for a quick answer.

Want to know more about dyslexia? Let’s fact-check some common myths about dylexia.

"Dyslexia was invented by Nazis" and other weird dyslexia web searches - Defeat Dyslexia

[…] What is dyslexia? […]